"We are one human family, on one fragile planet, in one miraculous universe, bound by love."

Tuesday, May 23, 2006

¡Ay, caramba!

Yet English has never been officially declared our national language. We’ve apparently never before thought it necessary to have an official national language. In fact, in recent years the movement has been toward trying to recognize and honor the multiplicity of languages spoken by U.S. citizens with bilingual and multi-lingual services proliferating. English certainly predominates in American discourse, but do we really need to call it the one true American language?

Christianity has been the religion of the majority of Americans, and one form or another of it was the religion of most of our forebears. Should Christianity be named our national religion? Should jazz, or country and western, or rock and roll be declared our national music? Should meatloaf and mashed potatoes or the greasy diner cheeseburger be declared the national meal?

Of course, the "melting pot" metaphor has long been used to describe the American ideal. They come to this country from wherever they're from and, in the great melting pot that is American culture, become like us. This model has encouraged immigrants to assimilate, to actively strive to be absorbed into the larger dominant culture, to let go of the cultural norms of their homeland and to adopt the norms of America. The arguments for an official national language draw from this longstanding tradition—we’re told that naming English as the national language will aid the assimilation process and increase unity in our country.

And this all might sound good on the surface, yet the underlying assumptions are inherently racist. That's because the "us" who "they" must become like are almost invariably white, Anglo-Saxon, heterosexual males. I know because I am one and the cultural norms that go largely unquestioned in our country are based on, and cater to, people who look and sound pretty much like me.

If you're also a heterosexual, European-American male you may not know what I'm talking about—that's why it's sometimes called "invisible white privilege." We don't usually see it because we're so fully immersed in it—like a fish in water—that we don't need to be aware of it. But just ask someone who looks, sounds, or acts differently and they can tell you how difficult it is to hear over and over again, "you are welcome here as long as you become like us—in other words, as long as you become somebody else."

Sociologists have long suggested that the metaphor of the melting pot—which was always more of an ideal than a reality anyway—should be replaced by the image of a "tossed salad" or a “smorgasbord” in which each of the individual elements retains its own uniqueness while creating together a richness that none could achieve on its own.

And if only unconsciously, the dominant majority culture recognizes this. Who would eschew sushi, tacos, bagels, or pizza simply because they’re not “American” foods? Where would we be without espresso and chai? Wouldn’t we be the poorer without the mambo of Tito Puente, the reggae of Bob Marley, and the symphonies of Beethoven?

According to a recent Washington Post article one in three U.S. residents—and nearly half of the nation’s children under five—are members of a racial or ethnic minority. This suggests that in the not too distant future the demarcations between majority and minority will be getting blurry. Is this what’s feeding the sudden urgency for a national language? As Sen. Barbara Boxer asked during debate on the Senate’s resolution, “Are we that insecure about ourselves?” If so, and if we give in to that fear, we will all be the poorer for it. Oye gevalt!

In Gassho,

Rev. Wik

Monday, May 15, 2006

To Savor or To Save?

Anyway, I was sitting in our sanctuary as these cool/hot sounds washed over and through me and I started thinking about all the other clubs and concert halls around the country—and the world—where people were at that very moment listening to other incredibly talented musicians. I started by thinking about other jazz concerts, but quickly realized that while I was listening to Stan there were folks also listening to country, and bluegrass, and opera, and rock, and hip hop, and táncház, and klezmer, and reggae, and salsa and every other musical style known to humankind. And I felt myself connected to each and every one of these other aficionados, and for a moment, it was as if I could hear all at once the music they were hearing and could feel all of their joy. Tears came to my eyes.

And then a second window opened in my soul and I began to hear the sounds not of music but of what the Bible calls “weeping and gnashing of teeth;” I heard the moaning sounds of mourning. During the couple of hours I’d been at this concert roughly 7,200 people had died on our planet, and who knows how many other people had experienced who knows what kinds of tragedies? While I sat listening to music there were people dying of AIDS, and hunger, and domestic violence, and war, and overdose, and suicide, and cancer, and accident, and neglect, and exposure, and murder, and every other way people die in our world. (Not to mention all the people who were right then experiencing racism, and heterosexism, and sexism, and poverty, and every other kind of oppression; people who were losing their jobs, and their families, and their hope—all the people who were suffering in all the ways we humans can suffer.) And I felt myself connected to each of these people, and the people to whom they are connected, and for a moment it was as if I could hear all of that agony and feel all of their pain. You’d better believe it—more tears.

And the question: What should I do? Should I keep sitting here listening to music when there’s so much that needs doing? What a luxury to be listening to music when there were people who were at that very minute suffering terribly! Shouldn’t I be doing something? I started to become overwhelmed with guilt and despair.

E. B. White—the renowned Maine-based New Yorker essayist; author of such classics as Charlotte’s Web, Stuart Little, and of course, Strunk & White’s The Elements of Style—once succinctly summed up life’s fundamental problem:

“If the world were merely seductive, that would be easy. If it were merely challenging, that would be no problem. But I rise in the morning, torn between a desire to save the world and a desire to savor the world. That makes it hard to plan the day!”

The Unitarian Universalist tradition I serve encourages us to embrace both those things that need saving in our world and those which call out to be savored. White’s problem is our problem—we don’t really get to choose because it’s a both/and proposition. Life demands both our best efforts and our deepest appreciation.

So I continued to take in the sounds of Stan Strickland and his band and tried to keep open that connection to both the joys and sorrows of life. That way, when I do the things I can do to try to make this world a better place, I know there’ll be a song in my heart.

In Gassho,

Rev. Wik

Tuesday, May 09, 2006

The Temple & The Meeting House

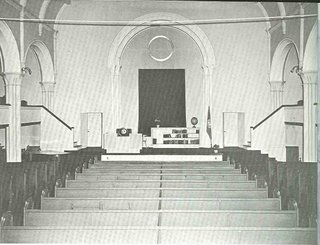

One element of the tremendously exciting experiement in liberal religion known as the Charles Street Meeting House was the transformation of its sanctuary. Its minister, the Rev. Kenneth L. Patton, argued that there are essentially two kinds of religious buildings: the temple and the meeting house. The meeting house is familiar to anyone who's grown up in New England. Largely devoid of any ornamentation, it presents a blank canvass. As Patton wrote in his classic 1964 work A Religion for One World, the meeting house is,

"simply a place of meeting. It is a shelter for fellowship. Its emptiness is to be filled with people and invites the inner quietness of the worshipers. The building says nothing. If anything at all is spoken, it is by the people gathered in it. Its emptiness does not intrude an outer form or dication upon the inner light of the attendent." (pp. 85-86)

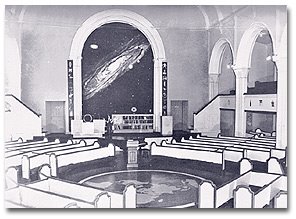

The other form of religious structure is the temple. Of this he wrote,

"The temple is just the opposite. It has a central theme or meaning in its dominant architectural symbol, and it is often lavishly decorated with related symbols and art. . . . The temple itself is an expression of a vision of reality and life. . . . [I]nstead of being merely the bare room in which a sermon is delivered, the temple preaches its own sermon through architectural and artisitic voices." (p. 86)

One of the first things Patton and the congregation did was to transform the Charles Street sanctuary from a meeting house into a temple. The totality of this transformation can be seen in these pictures. You can see the pews moved into a circle, surrounding an inlayed imaged of earth, so that the parishioners can see one another and know themselves to be representatives of the whole human race. You can see, too, the painting of the Andromeda Nebula in the apse which was balanced by a mobile of the atom at the other side of the sanctuary, so that the parishioners know their place in the cosmos as between the atom and the stars. The altar is a bookcase, filled with the world's scriptures, poetry, philosophy, and science. Adorning the walls are symbols of humanity's strivings, and art reflecting humanity's yearnings. Truly a temple of a "universalized Universalism."

The Unitarian Universalist Association sold the Charles Street Meeting House in the late 1970s. Today it houses not a worshiping congregation but offices and shops. This temple is no more. Yet the vision lives on, not just in congregations like the First Unitarian Society of Schenectady, NY but also in every congregation that prominently displays the symbols of major world religions. There was more to it all than this, of course, and I plan to come back to Patton and his vision in the days and weeks to come.

In Gassho,

Rev. Wik

[P.S. -- For more information on Patton and the Meeting House you can check out Kennan Pomeroy's research paper: Kenneth L. Patton: A Citizen of the World.]

Sunday, May 07, 2006

A priest, an imam, and a rabbi walk onto a soccer field . . .

The biggest hurdle, as of now, is finding a good date. Friday is the day of prayer of Muslims; Saturday's out as it's the Jewish sabbath; and Sunday would be a tough day for the Christians. Still, if they can work this out, can world peace be far behind?

In Gassho,

Rev. Wik

Thursday, May 04, 2006

Speaking Truth to Power

And just before watching it --or immediately after--you must also check out fellow UU blogger Philocrites' very insightful piece "Bush, Colbert, Lear and the Fool."

As a one-time "holy fool" I'll just add to Philocrites' comments with two quotations about the clown, the fool, the trickster:

"Why is it that fools always have the instinct to hunt out the unpleasant secrets of life, and the hardiness to mention them?" (Emily Eden)

"Jesters do oft prove prophets." (Shakespeare)

Tuesday, May 02, 2006

Introductions

"Here is Edward Bear, coming downstairs now, bump, bump, bump on the back of his head, behind Christopher Robin. It is, as afar as he knows, the only way of coming downstairs, but sometimes he feels that there really is another way, if only he could stop bumping for a moment and think of it. And then he feels that perhaps there isn't. Anyhow, here he is, at the bottom, and ready to be introduced to you. Winnie-the-Pooh."

I've always loved this passage, the first paragraph of the first chapter of Winnie-the-Pooh. I used it as the reading for my first sermon in my first church, the Unitarian Universalist congregation I have served for the past eleven years, the First Universalist Church of Yarmouth, Maine. It seems like such a good way to introduce the idea of introducing oneself.

So here I am, introducing myself to whoever you are reading this. My name is Erik Walker Wikstrom and I am, as I've said, currently the pastor of the First Universalist Church in Yarmouth. In August I'll be moving to serve a new congregation, the First Parish in Brewster, Massachusetts. These days I am filled with both a lot of sadness about leaving Yarmouth, and a lot of excitement about arriving in Brewster.

I'm also filled with a lot of thoughts--musings about the meaning of life, about the state of politics in the United States, about the condition of our culture, about movies, and comic books, and parenting, and God, and . . . So I've decided to join the bloggosphere.

It is my hope/plan to post here at least weekly, more often when there's something worth saying. I hope, too, that you'll come back often and post your own thoughts.

Yours, in Gassho,

Rev. Wik